Screams From The Crypt: Val Lewton Spotlight

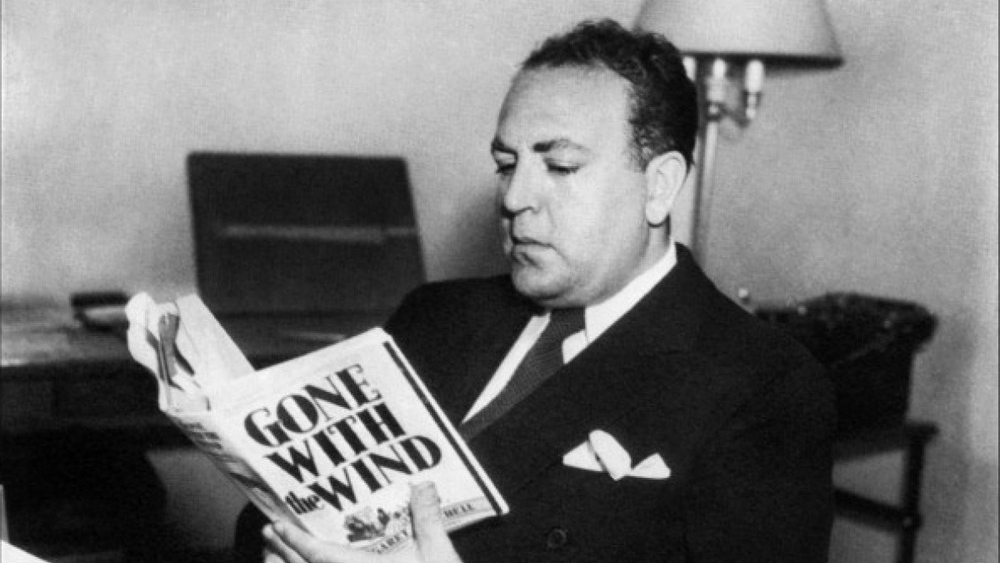

Adjacent to MGM, Paramount, Warner, and Fox, there was RKO Pictures; out of the big five studios, most of us associate RKO with Orson Welles and Citizen Kane. But due to the poor theatrical returns of Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons, there was a new mantra at RKO, “showmanship not genius.” Enter Val Lewton, who before his tenure at RKO was working what would seem to be a dream job, working under to tutelage of magnate producer David O. Selznick. However, Selznick’s tyrannical acumen drove Lewton away from the splendor of projects like Gone with the Wind to head a special unit RKO established to make quick, affordable, and profitable movies for their newly minted production house.

These are films that maintained creative autonomy from the producer as well as distinguished the directors attached to each title, which, in their own right, are standalone classics. The seemingly garish titles of his seven chillers, Cat People, I Walked With a Zombie, The Leopard Man, The 7th Victim, The Ghost Ship, Curse of the Cat People, The Body Snatcher, Isle of the Dead, and Bedlam, served as a jumping point for atmospheric, intelligent horror. In some ways it was reverse exploitation, Lewton would get a silly title and in return convert a dopey moniker into a mature, and intelligent horror film; relying on atmospheric scare tactics and (relatively) bloodless frissons to staggering effect.

The small wonder of an auteurist producer wasn’t the sole reason these movies rose to prominence as Lewton fueled the careers of directors such as Jacques Tourneur, Mark Robson, and Robert Wise. French ex-pat Jacques Tourneur would helm the best of the Lewton films starting with their maiden feature Cat People. Innovation is inspired in the face of contrast. And in the boys club of horror, Victorian decor, and monsters, Cat People is set in a modern-day New York, playing on the provincial notions of young Serbian woman who believes that she’ll transform into a panther and devour her lover because of an ancient curse.

The biggest takeaway from the first of the lot would be the mainstay of the following features; the fear of the unknown, and the power of suggestion. Cat People is scary because we don’t even get a trace of the titular implications, aside from the aesthetic fashionings the scares are so affecting because there’s a stalwart dedication to the characters and the substance of belief. Whether or not Irena (Lewton regular Simone Simon) actually transforms and eats people is beside the point, what we’re sold on with Cat People is her belief in the curse. The iconic pool scene still delivers a jolt, and the picture also gave way to the now infamous fake-out scare, or (irony aside) the “cat scare,” which for the sake of spoilers I won’t go into detail here, but, for the record, doesn’t involve a cat.

Riding off the success of Cat People Lewton’s team (including Tourneur and editor Robson) would take on an even more campy title that sounds like it was pulled from a supermarket tabloid, I Walked With a Zombie, which in my opinion stands as one of the best horror movies from the period. Mounting the silly but apt title with a script modeled after Jane Eyre, it tells the story of nurse Betsy Connell (Frances Dee) who is dispatched to a remote island in the Caribbean. Here she turns to voodoo to care for a catatonic woman while falling for the patient's husband in the process.

Tourneur and Lewton turn the narrative perception by tweaking the atmosphere toward the rituals of voodoo, and a queasily articulate air where death and the lingering notion of unease lurk in the shadows. The undead are malevolent only in the misguided cultural mores of the film's protagonists, poignant and moodily realized I Walked With a Zombie offers a unique perspective where death is the answer, and nobody wins.

With eight features as credited producer, Lewton and his crew both in front of and behind the camera had a system that was economical and efficient, so, when RKO paired Lewton with horror star Boris Karloff, he took that as an affront. These trepidations went to the wayside as Karloff and Lewton’s three films would be some of their finest work, and he and Lewton became close friends in the process.

Based on a Robert Louis Stevenson story The Body Snatcher stands as one of their best collaborations, and it’s also a notable feature because alongside Karloff is Bela Lugosi in what would be the last time the two would share the screen. Karloff shines as the malevolent John Gray, a scheming cab driver that happens to moonlight as a grave robber. Karloff settles into the role of Gray with a zealous enthusiasm as he was always striving for more dimensional characters than the classic monsters that made him famous, and in the Lewton tradition, his slyly sinister nature is played out superbly understated.

The constant thread through all of Lewton’s horror films is the subtle fashion of realizing the nature of fear. Using the dated ethics of medicinal practice (which is in its own right terrifying) the implications of the story carry substantial weight, but the layers of moody atmosphere thanks in part the director Robert Wise make the material all the more substantial.