The Wages of Friedkin: Sorcerer at 40

You know the little pain that you feel in the back of your head when you admit to liking a remake more than the original? For me, that went away because of Sorcerer. It might not seem fair to frame William Friedkin’s 1977 film with the same context we currently associate with remakes. Sorcerer without doubt retreads some of the same ground as H.G. Clouzot's classic The Wages of Fear, but Friedkin took the challenge and made it his own. Which is why it’s one of the few films that eschews that conundrum of art, entertainment, and the tenet of originality.

Friedkin, born from the artist era of Hollywood, has proven himself as such while having his feet rooted in genre films. His success, however, hasn’t landed him in the spotlight like Spielberg, Lucas and Coppola did with their respective films. Friedkin's work feels so uncompromising, and the fact that Sorcerer’s poor box office performance is partly attributed to having opened up a month after Star Wars affirms that steadfast dedication to his rugged aesthetic, despite the changing tenor of public preference. People were going out for Rocky, Jaws, and Star Wars, not Cross of Iron, Opening Night, or Sorcerer. Friedkin took the momentum garnered from The French Connection and The Exorcist and poured himself into what should have been seen as one of the best films of 1977. Instead, it derailed his career for years to come, but Sorcerer stands as a testament to his resolve and vision. The film is a breadth of superlative components that are classic and contemporary, gritty realism against a sweeping scope. Friedkin saw the landscape like John Huston, and Sorcerer is the kind of high-stakes adventure in the spirit of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. And in borrowing from its core inspiration, The Wages of Fear, we get something that’s just as invigorating as the new wave of blockbusters that surpassed it.

Sorcerer plays on the elemental draw of a wilderness adventure, but it takes pastoral romanticism for a form of lyrical misanthropy, and it’s international cast boosts the cutting political growl that’s not too far underneath the narrative. Sorcerer delivers a unique and often unfulfilled promise, a mature and vibrant thriller, with action and intelligence. There’s a strange, indefinable wedge in the range of expression. There’s an awkward stoicism in the dialogue and characters that lend to the knuckle-gnawing suspense which folds into moments of surrealist imagery.

Friedkin’s sense of the real and ethereal are fully formed and operating at a calibrated pace. The four leads are desperate men who find refuge in a South American hellhole; it’s a hot and sweaty place elevated to Alighierian proportions by a raging refinery fire. Scanlon’s (Roy Scheider, a role originally intended for Steve McQueen) psychological breakdown later in the film becomes a surreal deconstruction of the climactic structure; the title evokes a sense of mysticism and the film grounded in its elemental imagery and political urgency, and yet it feels fevered and hazy.

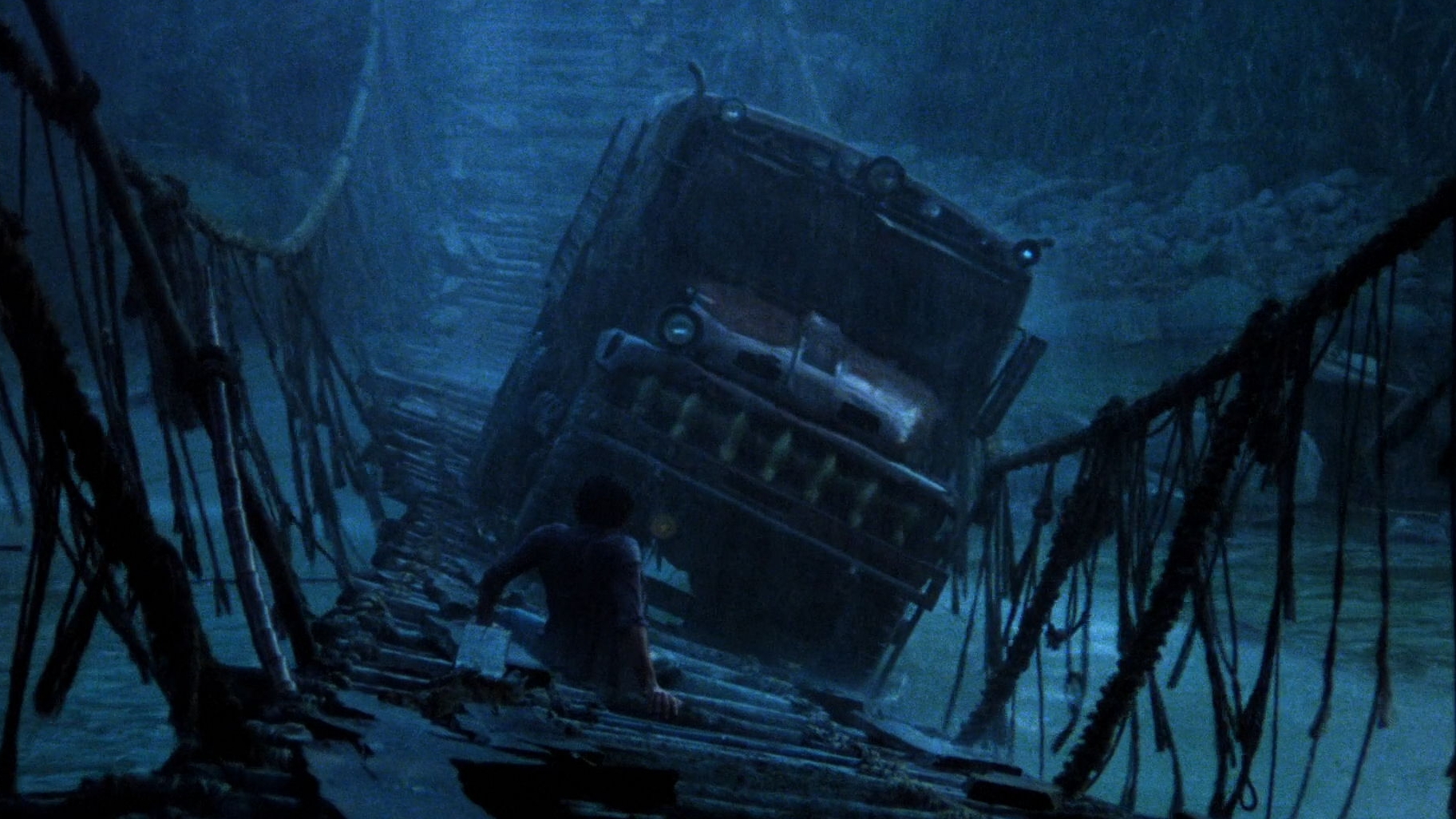

In the climate of the New Hollywood movement, there was a tremendous evolution in style, especially from Friedkin who thinks like a troubled journeyman. He makes Sorcerer with an ambition and a slyly cultivated sense of style unseen before or after. Ebbing from tradition is one of the film's strongest aspects, the synth pop cadence of Tangerine Dream’s atmospheric score. The whimsical expression from Tangerine Dream satisfies both sides of the film, bolstering its mechanical emotionally distant aesthetic, but bold enough to accentuate traditional frissons of suspense, and action, it’s impossible to imagine the movie without its score. Its interweaving threads of ambient accentuation play against the impossibility of the film's powerful imagery: a truck crossing a suspension bridge with whipping torrents of rain and driftwood blowing about, and the procedural skillfulness of blowing up a fallen tree with the crudely effective explosive device whittled for its timing. Most memorable, the montage of truck repairs as the guys prepare their vehicles (or gas-powered tombs?) to transport nitroglycerin . Details like hammering in the steel core wire coil into the rotating drum, calibrating the radiator fan, and mounting new mirrors; these trucks are characters in the movie, and it’s no coincidence that the titular truck, Sorcerer, has the devilish smirk of a tiki head.

Sorcerer had the battered reputation of being one of the movies that dismantled the directors' era, alongside Heaven’s Gate and New York, New York. Sorcerer was another entry from the wunderkind new wave directors who went over budget and didn’t fare well with audiences upon release. While there's always been a minor cult surrounding the film, Sorcerer is an unlucky enigma whose long overdue renaissance has arrived. It was a bomb and afterward the movie was an overlooked classic. Now we can take 'overlooked' out of the equation.